»They say they want to cut my throat«

Hate and deadly violence has forced many LGBT persons to flee Uganda. Kasha Jacqueline Nabagesera stays on, but nowadays she never leaves the house alone. Annika Hamrud meets a world-famous activist.

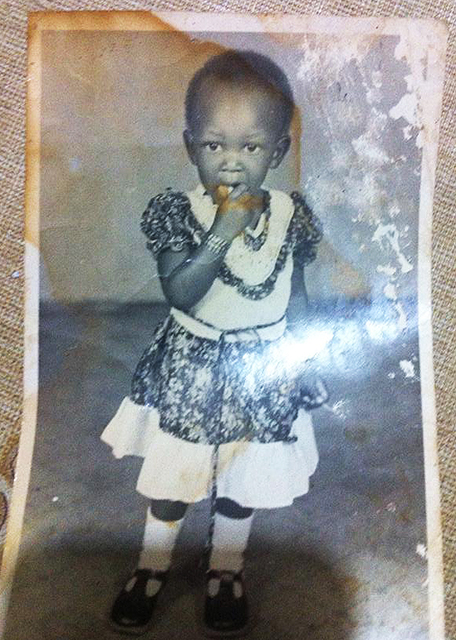

Kasha has changed her sneakers for flip-flops and put on a cap that conceals her long dreadlocks and her thin legs stick out of her short trousers when she dances down the stone staircase, enacting scenes from the 1965 movie The Sound of Music. The unlikely setting is a 19th-century Austrian palace, Schloss Leopoldskron, where the film was shot, a film that Kasha has seen every Christmas in her homeland Uganda since she was a small girl.

It’s june 2015. Thirty-five year old Kasha Jacqueline Nabagesera is in Austria to take part in a weeklong international LGBT (lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender) conference with participants from 33 countries. In the last few weeks she has also been to Germany and Norway to discuss human rights.

After the conference in Austria, she will make a short stop in Kampala before continuing to New York City for a three-week stay, where she will be Grand Marshal at this year’s Pride Parade, together with the British actors Derek Jacobi and Ian McKellan, and the activist J. Christopher Neal.

“I will not leave Uganda until I have reached my goal. But then I will go!”

Later, when we meet again in Kampala, she talks about her mixed feelings when she sat in an open car in the enormous New York Parade. The massive cheers were overwhelming, and the contrast to the hate in her native country were glaring. She was glad that she had her American-Ugandan friends in the Parade and felt good about returning home to plan her own Pride – Uganda Pride.

Kasha Jacqueline Nabagesera is famous all over the world as a representative for Uganda’s LGBT movement. In November she’s in Sweden to receive the Right Livelyhood Award – also known as the alternative Nobel Prize – for her fight for human rights for LGBT people in Africa and the world at large.

She comes from the country where the Nile River has its source, a country with rainforests and gorillas. But Uganda is also a very poor, landlocked country in central Africa, which is informed by its colonial heritage and where religion has a strong hold on people. It is also a country where there are gigantic refugee camps, for people who have fled the wars in Congo and South Sudan – and for internal refugees who have fled the terror of Joseph Kony’s Lord’s Resistance Army.

Here, Kasha and other activists have built a LGBT movement without parallel in the rest of Africa. She has made a big difference for many Africans. But she has also impressed the world. Almost certainly, no other LGBT person has made such a strong impression on world leaders as she has.

»The work she has done, which has led to awards and notoriety, has come at a high price; she lives under constant threat.«

Kasha has spoken in both the European Parliament and the UN and she has been invited to the Swedish Parliament several times. She has received many awards before, from the Swedish magazine QX’s special prize to Amnesty International’s Martin Ennals Award.

It is also certain that the work she has done, which has led to awards and notoriety, has come at a high price; she lives under constant threat.

Still she giggles. The threats are an everyday occurrence. She has even been assaulted in central Stockholm by Ugandans who claimed that she and her colleagues have sold out to the mzungus (the whites) in the West.

“Even at the human rights conference in Germany last week I was threatened by African and Arab delegates,” she says.

“There were five Africans who almost wanted to kill me. But I said, ‘My God, you’re only five, I’m used thousands of people wanting to kill me,” she says.

Kasha is a lesbian, but she never was in the closet and consequently she doesn’t have a coming out story. Already at the age of seven, her teacher told her that one day she was going to be kicked out of Uganda. She didn’t behave like other girls and her mother let her wear the same school uniform as her brother, when she didn’t want to wear a skirt.

»Supporting her lesbian daughter in everything made Kasha’s mother unique in Uganda.«

Time and again, she was expelled from school, always for the same reason, writing love letters to other girls. At university, she studied accounting, IT and marketing. The university called her mother to tell her that they were going to expel Kasha, but Kasha’s mother had grown tired of moving her daughter around and said that Kasha was ill, asking them to let her finish her studies. Kasha was very hurt by her mother saying she was ill, but it was also a stratagem.

»Kasha comes from a royal family and is a princess of Buganda.«

Supporting her lesbian daughter in everything made Kasha’s mother unique in Uganda. In addition, Kasha’s family was wealthy, which made things easier in a poor and corrupt country such as Uganda. Kasha comes from a royal family and is a princess of Buganda. Her father was a prince and the deputy chief of the Ugandan Central Bank, while her mother was one of Uganda’s first programmers, also employed by the Central Bank.

Kasha’s voice is husky and muffled as she talks about her childhood and adolescence. She speaks with a distinct Ugandan accent, but her vocabulary differs from the “Uglish” (Ugandan English) that is otherwise heard in Kampala. She was allowed to continue her studies, but posters were set up telling people to avoid her. At his introductory lecture for new students, the chancellor warned other students not to be seen in her company.

Slowly, Kasha realized that the life that she and her friends led was criminal. But it wasn’t until 2001 that she began to find out more. An internet café opened on campus and she went there and asked how she could find out more about homosexuality.

“The more they exposed me at university, the more LGBT people I got to know. It was like marketing for me. We were a group of girls who partied together. Only then did I realize that what we were doing was illegal.”

Kasha continued to search for information on the Internet. After she had read up on homosexuality in Africa, she got drunk.

“I told my friends in the bar what I had learnt and they looked at me, astonished, and said, ‘But Kasha, didn’t you know?’”

»In 2003, they were outed by the tabloid press with names and pictures. After that they were attacked, many of them raped and beaten.«

The group started to find out more about the international LGBT movement and Kasha decided to take an online course in human rights at Boston University.

They were 40–50 women who occasionally met at the bar. In 2003, they were outed by the tabloid press with names and pictures. After that they were attacked, many of them raped and beaten.

“That’s when I decided to become an activist. Most of the others in the group were disowned by their families and couldn’t take more risks. I was prepared to go public. There were two other people who were prepare to do the same. One was my cousin, the other Victor Mukasa.”

Her cousin is a DJ in Kampala, but nowadays she has given up activism. Victor, who is a trans man, lives in New York today. They took a long time to think up a name for themselves. Eventually they decided on Freedom and Roam Uganda – FARUG. That was their goal, to be able to move freely and be themselves without fear.

The group started to contact human rights organizations all over the world.

“We got much negative reactions in Uganda, but also some positive. From abroad the reaction was: ‘Where have you been? We have been looking for you!’ We started using the term LGBT for ourselves. We included the T just because we had seen it on the Internet. But we didn’t know what it meant. Not until in 2006 did we start talking about gender identity. We didn’t know anything about activism. Many of us in FARUG had not been to school and many had been kicked out of their families and were poor.”

Kasha describes how the National Ugandan Agency for Education wanted to fight homosexuality in the schools. They saw particular “problems” in the girls’ and boys’ schools, which are often boarding schools in Uganda. In 2004 all schools were ordered to investigate if they hade any gay students. Students were encouraged to inform against their friends. In one particular school, there was a girl – Paula – who was mentioned on everybody’s list of suspected homosexuals. She was degraded in front of the whole school, caned publicly and the principal called her parents. Paula committed suicide.

Everyone was happy, no one condemned the incident, not the women’s organizations, nor the Government, and the radio played music to celebrate.

“We realized that this could have happened to anyone of us,” says Kasha.

»The newspaper Red Pepper decided to spy on them. The journalist had even stolen pictures from Kasha’s private photo album.«

At the time, there was a popular programme about sex and relationships on the radio. Kasha and her friends decided to call the radio station and ask if they could make a programme. They got a positive response. They took calls from listeners and openly discussed what had happened to Paula.

“We received many crazy calls and then the papers started writing, and FARUG became known all over the country.”

Afterwards the group met a major setback. The newspaper Red Pepper decided to spy on them. One woman from the paper infiltrated FARUG. No one suspected anything. She visited Kasha’s mother, where several of Kasha’s friends also lived. A few months later the paper published the story, “Inside the Lesbian Den” ,eight pages of pictures from Kasha’s house, of her mother, her and her friends. The journalist had even stolen pictures from Kasha’s private photo album.

The newspapers realized that writing about gay people attracted readers. But the stories dried up and they started making things up. They wrote that Kasha ran a school where she taught students to be lesbians. They said that she had married at a ceremony on a beach by Lake Victoria. They wrote that she received loads of money from the West to “recruit” young people to homosexuality.

“They even wrote what day we were supposed to have married and named a priest! My mother was angry because I had married without inviting her to the wedding,” Kasha laughs.

She catches sight of a goose on the lake at the Schloss and we observe it for a while. People come to picnic in the palace gardens. The weather in Salzburg is wonderful, with a sun that is as bright as the one that shines on the children in Sound of Music. Later that night, the participants in the conference gather in the palace’s basement pub. Kasha is the DJ. She takes requests, which she intersperses with Ugandan hits.

After Kasha and her friends started FARUG, a few gay men founded an organization called Spectrum. In 2004, Victor Mukasa started SMUG, an umbrella organization that represents the whole LGBT community in Uganda.

In 2005, there was a big campaign against poverty in Africa called GCAP – Global Call to Action Against Poverty. FARUG decided to take part, wanting to sign the appeal about debt cancellation and to make placards like the other groups, and they contacted the organization Action Aid, who welcomed them. But when Kasha and Victor came to the Freedom Square in Kampala they found that there was no space for them.

There was unease among the other organizations, because FARUG attracted the wrong kind of attention, and the organizers asked them to leave.

Kasha and her collaborators decided to report the incident. The fact that Action Aid had thrown out LGBT activists was embarrassing to the organisation and Action Aid decided to establish connections with FARUG.

Two months later, Ugandan police raided Victor Mukasa’s house and arrested a Kenyan friend who was visiting. The police confiscated all FARUG documents they could find and the activists decided to sue the police, which led to their first victory. The court said that the police action was illegal. But the situation became more and more insecure for Kasha. Action Aid decided to take her out of the country.

“I was asked to pick a country and I chose South Africa. I was given a two-year internship at an organization called Behind the Mask. I also studied media there and how to work in a hostile environment.”

The time in South Africa was like a school for Kasha. With her new knowledge she was able to develop FARUG further. It was at this time that she came in contact with RFSL – The Swedish Federation for Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual and Transgender Rights – and was invited to Sweden.

“I addressed the Swedish Parliament. Then I invited Swedish activists to Kampala and they flew down for a week. We came up with a beautiful project that is still running today. It has been an amazing cooperation.”

»I have lost so many friends since the first years, Now I am alone much more often.«

In 2009 Kasha sent a group of activists to Sweden and for the first time a gay Ugandan man took part, although he chose to stay on in Sweden upon learning that the police were looking for him in Kampala. For every year, more and more Ugandan activists sought political asylum when they came to RFSL:s courses. Today it is very difficult to get a visa to Sweden because so many have sought asylum. But many activists have already left Uganda.

“I have lost so many friends since the first years”, Kasha says. “We are only two left. The others have died or left the country. Now I am alone much more often. The activists working today have come in the last five years. Of those in the beginning, almost everyone left for the UK, and a few for the US.

»I thought that we were going to die. I sat close to the door, in case I needed to run.«

“We had a brain drain, but you have to understand why people are defecting. We are a poor country. Many have been disowned by their families and have been threatened by their communities.

But things progressed and the activists felt that they were fighting a winning battle. But then people started arriving from the US.

“Our visibility was too much for a Christian organization called Family Life Network, which invited the leadership of its American organization.”

Kasha participated in a conference that the Americans held for various influential people in Uganda. For three days she listened to their hate against gay people. In the conference people said that the whole of the African continent was going to follow the activists in Uganda, if they became “a blueprint for homosexuals.”

“I thought that we were going to die. I sat close to the door, in case I needed to run. Some of the participants in the conference didn’t want to get close to me in fear of being infected.”

Immediately after the American visit, work started on a Government bill, which in the beginning was nicknamed “kill-the-gays” bill.

»Kasha is an activist from the moment she wakes up until she goes to bed early in the morning.«

There is really nothing that distinguishes Kasha the activist from Kasha the private individual. She is an activist from the moment she wakes up until she goes to bed early in the morning. And she takes part as much in the political work as in the partying.

Pride Uganda is one of the year’s highlights for Kasha. This year was the fourth year in a row when activists in Kampala organized a Pride Week, which goes on for several days and includes both seminars and parties, as well as a parade. This year, 2015, the celebration started on a Wednesday in August with a cocktail party for specially invited dignitaries, something that drew criticism from people who were not invited. But the fact that that people such as foreign ambassadors come to a pride opening on a roof in central Kampala shows that the gay movement in Uganda is being listened to by the rest of the world. (Read swedish article about Pride Uganda here)

On the Thursday, there were courses about transgender and health issues for the whole LGBT community, and on the Friday night, there was a party at which a Mr Pride and Ms Pride were elected to represent the LGBT community in the coming year. The party went on to the small hours, just like everything else during the week.

The Saturday was reserved for the march. The participants gathered in the botanical garden in Entebbe on the shore of Lake Victoria. For security reasons the place was kept until the day itself.

Kasha was dressed in a kilt, rainbow-coloured knee stockings and a top hat, and she wore rainbow feathers on her back. The international journalists flocked round her, but in the eyes of the other LGBT activists she is just

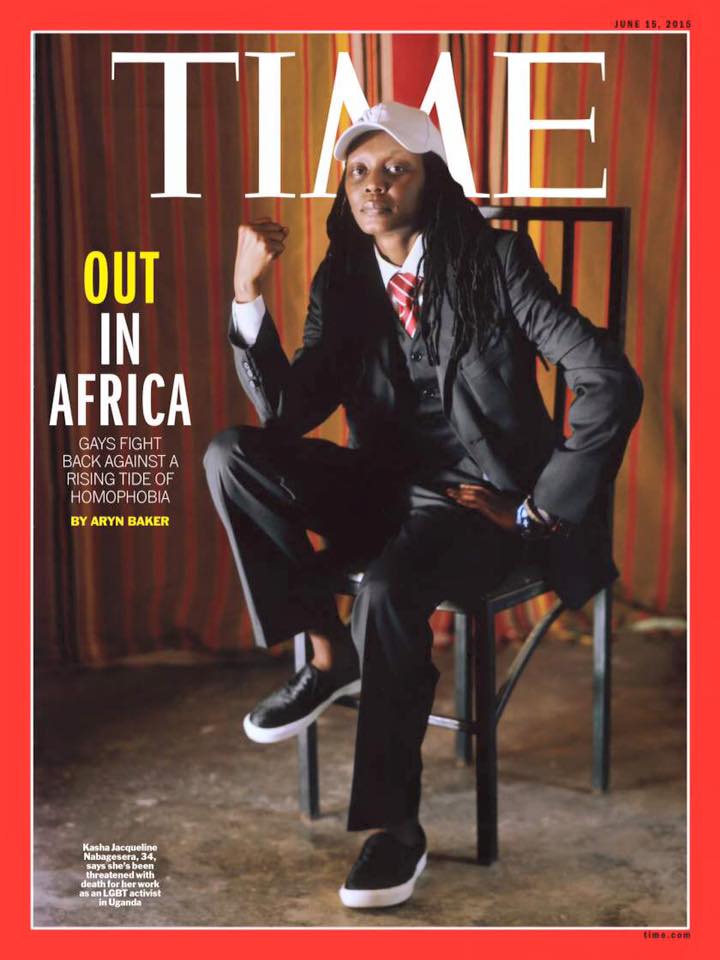

like all the others walking around saying hello to their friends. But she is not liked by everyone. Some think that she is doing too much work abroad and that all the vulnerable people at home are not getting the support they need. During my visit, several people wanted to talk to me about their ill treatment. They didn’t think that their situation improved when Kasha appeared on the cover of Time magazine. Others questioned what the money from abroad was used for. And others thought that Pride is a Western invention.

“I can’t make everyone happy,” says Kasha.

The couch in front of her television set is Kasha’s office. This is where she goes directly from bed. In the living room, there is also a table with a solitary photograph of Kasha’s mother, who died of a heart attack before she was fifty.

The only time that Kasha is able to work without being disturbed is at night, since there is always someone who wants to get hold of her in the daytime, both activists in danger and journalists from all over the world. Sometimes she cannot stand the journalists, especially those who just stay for a day and want her for a quick story. Nor is she very favourable towards scholars and university students, who take up her time for essays that she will never see.

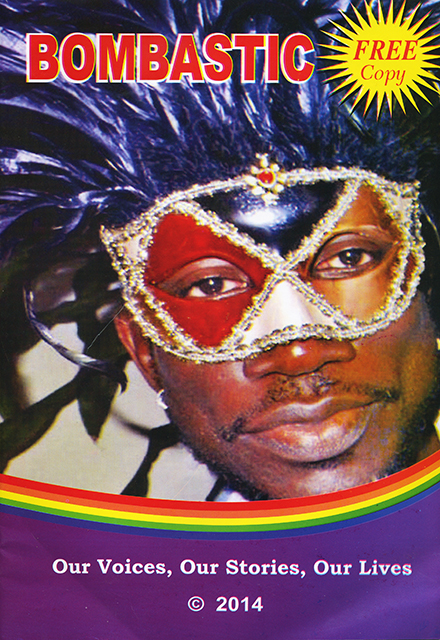

Two years ago she left the FARUG leadership. Now she runs the magazine Bombastic and the website Kuchu Times. Every day, the editorial staff meets in a shed at her place. They don’t have any furniture yet and sit on the floor around a simple mobile internet router.

Two years ago she left the FARUG leadership. Now she runs the magazine Bombastic and the website Kuchu Times. Every day, the editorial staff meets in a shed at her place. They don’t have any furniture yet and sit on the floor around a simple mobile internet router.

Today Kasha’s main goal is to reach out and show that LGBT people are like anyone else. She wants to arouse the sympathy of the world around, make people hear other things than what the priests and preachers say about gays “recruiting children.” The Bombastic magazine is distributed by 60 activists throughout Uganda. In some places they have been arrested by the police, but so far everyone has gotten away safely. Recently Kuchu Times reached its millionth visitor.

Kasha moved to this house in 2013, when the anti-gay act was passed in the parliament. The place where she used to live attracted too many curious people and there were often rows. Every day a preacher stood outside the house. Eventually the landlord wanted her to move out.

The road to the house is almost impassable. If there ever was paving it has been washed away by the torrential rains during the rainy seasons. The garden with its tall palm trees is surrounded by a wall. Beneath the trees, there is a playground for Kasha’s nephews. The contrast to the intense traffic in the big city outside is striking.

“I feel safe here,” says Kasha. “But I can’t go out.”

A boda guy (a boda is a motorcycle taxi) buys her food and drives her car when she needs to go to a meeting or to the airport. Despite all the precautionary measures, the car is adorned with rainbow stickers and during Pride Week it sported a flag.

Kasha is a political superstar, but it is not something that you think of in her company. She is happiest at the pub and for a couple of years she ran a bar that was eventually closed down by the authorities. She works hard and has thousands of ideas, the latest one being to open a laundry that will employ kuchus (LGBT people).

»At home she also has an everyday life with a girlfriend, a cousin and the cousin’s boyfriend. And the dog Arzy.«

Kasha works all the time, but at home she also has an everyday life with a girlfriend, a cousin and the cousin’s boyfriend. And the dog Arzy. The atmosphere is reminiscent of a collective of young people. In the collective, both English and Luganda are spoken, and they often change language in the middle of a sentence. There is a steady stream of visitors.

Kasha says that she longs to sit down and watch television by herself. She wants to have children and has applied to adopt. When she works, sitting on the couch in her living room, there is always an American crime series or a soap opera on, interspersed with international news.

Sometimes she gets sick of all the e-mails and Facebook messages. Above all, she is annoyed by everyone who tags her, something that leads to her messages and private pictures ending up in the tabloids. Every careless tagging constitutes a risk to her security.

There are new threats all the time.

“Often they call and play religious music, while others say that they will cut my throat,” she says.

After a piece in Time magazine earlier this year, with Kasha on the cover (see picture above), many well-known bloggers threatened her openly.

“One woman on the radio said that I had placed a demon in her,” Kasha says.

Still, her situation is better now than it used to be. She used to live in hiding, has been smuggled out of Uganda and has spent long periods abroad and in secret locations inside Uganda. Her contacts with international relief organizations and LGBT activists around the world guarantee her security. It is both a matter of funding and of making her untouchable for the authorities, since the whole world is watching.

»Sweden is my second home. It is the best place to live, if you ignore the racism.«

But her sense of security and her stubbornness come from her personal background. Although the support from the world is now of the utmost importance for her, it was the security that her mother gave her when growing up that made Kasha more daring than others. Stubbornness is what makes her stay on in Uganda. She will not stop working until Uganda is a country where LGBT people can move around freely without fear.

“I will not leave Uganda until I have reached my goal. But then I will go!” she says, laughing.

She has two favourite places that she returns to every year. One is Sweden, the other New York. “Sweden is my second home,” she says. “I have visited so many places there … It is the best place to live, if you ignore the racism.”

The struggle has taken its toll on Kasha. It hurts when she thinks about David Kato, the first openly gay man among the activists. He was killed in 2011, the year after the new weekly magazine Rolling Stone published a list of a hundred LGBT activists under the headline “Hang them.” The activists sued the magazine and won, and it was closed down. Although the magazine was small, it did a great deal of harm.

“David was so sweet and always kind. We could have an argument and then he would suddenly ask you how you were doing.”

Kasha hardly knows how she managed after David’s death. She had to go to the morgue to identify him. He had received a blow to the head and half of his skull was missing.

“I needed to go to the bank to get money to buy a suit, go to the funeral parlour and identify him at the morgue. The media wanted to talk to me and the police were after me. I drank so much. It was crazy and then we got a homophobic priest at the funeral. I just stood there and saw that there was chaos and I don’t know what happened. I lost my breath and started sweating. I remember that I told David’s mother that we would bury him ourselves. In the evening I saw what had happened on TV, but I don’t remember it myself.”

»The media wanted to talk to me and the police were after me. I drank so much. It was crazy.«

But the things Kasha herself cannot remember was filmed. She walked up to the Anglican village priest who was preaching about the evils of homosexuality and grabbed his microphone. She walked away, speaking in the mike: “We didn’t come here to fight. We just came her to bury our friend,” she said and went on, “Enough is enough. Enough is enough”. (See video clip here)

The murder of David Kato shook the LGBT community deeply and reached the international news. The media outed many people at the time and FARUG had to help everyone who was evicted from their homes.

The Government immediately said that the murder was not a hate crime, but within a few days a man was arrested. The sentence was quick, but there are still many unclear points in the case.

»The ”anti-homosexuality bill managed to do a lot of harm. Many people were arrested and even more people got harassed.«

The world had their eyes on Uganda for many years afterwards because the activists made sure that the world was informed about what happened to the proposed law. The “anti-homosexuality bill” was not only going to give long prison sentences to homosexuals, but also create a system of informers against gay people and making it illegal to let flats to gay people or to employ them. In spite of Uganda losing many foreign contributors who tried to stop the law by withdrawing financial aid, the bill was passed in Parliament in 2013 and came into effect in February 2014.

Just after the law came into effect, the first trans woman got arrested. She knew nothing about the law. There were others who left the country the same day.

A number of top lawyers worked on an appeal to the constitutional court. Not very surprisingly, the case was never taken up by the court. Instead the law was declared invalid half a year later on the grounds that not enough MPs had been present when it was passed.

Still, the law managed to do a lot of harm. Many people were arrested and even more people got harassed by hate mobs.

What is it like to be world famous?

“First of all, it is my security, but I also feel that it motivates other activists in their work. My awards have also helped me financially. I have been able to buy a car so that I can move around. Recently I was nominated for the Right Livelihood Award.”

Why is there more focus on Uganda than other African countries?

“It has to do with the activists, who are very vocal. But the oppression is not more severe in Uganda than in countries such as Gambia, Nigeria or Kenya. Most of the homophobia comes from religion, both from the Bible and the Quran, and it is worst in the former British colonies.”

Kasha is happy that she has long-term visas to several countries. She can leave Uganda whenever she wants. But others who need to leave the country have a tougher time.

Soon the campaign leading up to the Presidential election in 2016 will start. There is a risk that the bill will be put in front of the Parliament again.

“That is why we have to make people aware.”

How do you find the strength?

“I can handle it.”

She giggles and adds, “Aluta Continua.”

The fight goes on.

Annika Hamrud

Swedish writer and freelance journalist.

Translation and adaption Peter Samuelsson

Läs mer

Read more on lgbt and Uganda on Ottar.se: