Period politics

Periods come at a cost: missing school, unpaid sick leave, health risks, and being ridiculed and silenced. This is the result of a greater shame around menstruation. So what is needed to break the taboos around menstruation? Ottar meets with menstrual activists and menstruators around the globe to discuss.

“Everything is connected: money, gender, power – and menstrual shame.” The words are from the book It’s Only Blood: Shattering the taboo of menstruation by journalist and author Anna Dahlqvist. It is from a chapter detailing how some girls in places like Kenya and Uganda have sex with older men in exchange for money, in order to be able to afford menstrual pads. Because nothing could be worse than blood-stained clothes.

»It’s so fantastic that we can give birth, but it’s unthinkable that anyone should need to see the evidence of our fertility«

Anna Dahlqvist

“It’s patriarchy in a nutshell,” Anna says on the phone from her native country Sweden. The book was born out of her own rage after reading about girls in South Africa missing school as a result of not having the resources to manage menstruation. “It’s the height of oppression, that we should be punished for our reproductive ability. It’s so fantastic that we can give birth, but it’s unthinkable that anyone should need to see the evidence of our fertility”, she says.

Around two billion people around the world menstruate, or an estimated 300 million people on any given day. You would think that it would be viewed as the most natural thing in the world, and yet it’s not. So where does the shame come from? “Historically, it’s been seen as something strange and very difficult to interpret. It’s quite a powerful thing, for a person to bleed without dying or being sick,” says Anna Dahlqvist. “When that mystery was adapted to a patriarchal worldview, it became a symbol of women’s subordination. You’re deviating from the norm of the male body.”

But there are many additional factors to compound the shame, believes Anna Dahlqvist. The blood comes from the vagina, which is associated with female sexuality, which is in itself seen as something shameful. It’s a body fluid that cannot be controlled, something otherwise associated with children. And with body fluids come notions of hygiene. “We’re meant to hide wee, poo, snot, vomit and blood – and this blood just keeps on coming”, Anna says.

For Anna Dahlqvist, talking about menstruation in the context of human rights is key. Most central in relation to menstruation, she explains, is the right not to be discriminated against as a result of your sex. But the right to education, the right to work, and the right to life and health are highly relevant too. Consider, for instance, that it takes years to get a diagnosis for common conditions like endometriosis, which can make periods exceptionally heavy and the accompanying pain debilitating. Consider that, in some parts of the world, pieces of cloth used to collect blood are washed using dirty water and dried in secret corners where they are likely to go mouldy, all while factory workers and school girls spend days at home every month, losing out on both education and wages.

An estimated 2.36 billion people in the world lack access to toilets. 650 million don’t have access to clean water. In Kenya alone, one million girls miss an average of six weeks of school every year due to menstruation hygiene. Where pads are too expensive or simply impractical, girls resort to using everything from newspaper to grass, and reusable pads that don’t dry out properly, and become breeding grounds for infection. The consequences range in severity from itchy rashes and urinary tract infections to – if the initial findings of some studies are correct – over time potentially cervical cancer. If health is a human right, we need to talk about menstruation.

For Lillian Bagala, Regional Director in East Africa for Irise International, an NGO working to end period poverty and shame with their office based in Uganda, these issues are very real.

“Some communities see menstruation as a rite of passage, others as a sign that the girls are ready to be married off immediately. But there’s also a real lack of information,” she says. “And crucially, the lack of access to period products means that many girls drop out of school.”

In addition to ongoing education efforts and the lobbying of elected representatives to put in place clear policies on menstrual health, Irise has recently been working with what Lillian Bagala describes as a community engagement approach.

“We’ve got community champions who work with menstruation health awareness, and when we have the resources, we get the community champions to distribute the products and make sure that girls know where to go to ask for help when they need it,” she explains.

“We’ve seen that it really boosts these girls’ confidence levels. There’s so much appreciation accredited to a simple pad – a girl knowing that she is safe to go to school, that she doesn’t have to keep missing lessons.”

»So many women suffer from menstruation pain but don’t even get medication because of the shame«

Lillian Bagala

At the moment, Irise is working to spread the word in particular about reusable pads and cups – partly because they’re cheaper in the long-run, but also because disposable pads are so bad for the environment, including the local environment. Unfortunately, the water and sanitation hygiene (WASH) infrastructure in schools often leaves a lot to be desired, including shared toilets for boys and girls, many of them constructed out of mud.

But the work is paying off. For instance, some schools have put in water stations that the girls can use. On a wider scale, there’s the hope that knowledge sharing with other organisations might contribute to more effective initiatives on issues that are lagging behind in East Africa, such as menstrual pain management.

“So many women suffer from menstruation pain but don’t even get medication because of the shame,” says Lillian Bagala to Ottar magazine.

»If someone leaks through at school, it’s still the end of the world«

Camilla Mørk Røstvik

That shame, according to Dr. Camilla Mørk Røstvik, researcher at University of Leeds and Co-Investigator of the Menstruation Research Network UK, has been a constant for a very long time – and she is not convinced that it’s diminishing.

“There have always been people who insist that the stigma is getting smaller – in the ‘20s, in the ‘50s, and again now. And sure, we have more products and more frank advertising, and policy makers are getting involved. But if someone leaks through at school, it’s still the end of the world,” she says.

»If you look through an intersectional feminist lens, there are so many complex issues«

Camilla Mørk Røstvik

Camilla Mørk Røstvik is wary of western charities going to the Global South “evangelising” about eco-friendly period products.

“You need education, and you need sanitation facilities. It’s not just poverty – it’s people working in factories, people doing shift work, disabled people who simply can’t use a cup. If you look at all the minority perspectives through an intersectional feminist lens, there are so many complex issues,” she says, adding that the involvement of corporations is equally complicated.

“In an ideal world, education should be free from corporate sponsorship, but sometimes they do good work – often when no one else wants to. For 20 years, corporations have been providing products for schools in places where no one else did.”

We turn to Scotland and the Period Products (Free Provision) (Scotland) Bill, which was approved by the Scottish Parliament last year, meaning that now local authorities are legally obliged to ensure that period products are readily available to anyone who needs them. Camilla Mørk Røstvik says she was impressed with the way the bill was debated, yet she is uneasy about the celebratory framing of it.

“We’ve got to a stage where we’re celebrating Scotland, but are we just celebrating that it had so much poverty that it had to create this policy? It came about because of the stigma that’s still there in the 21st century – a stigma that always strikes me as very similar across the world,” she says.

“The media get a good story, and the corporations make money, so they’re happy. But what’s that doing for menstrual stigma? We vilify the menstruation huts in Nepal, and then we jazz it up in all sorts of ways over here, but why do we need to provide free products to these girls? It’s really all about fear of seeing blood.”

Jazzing up or no jazzing up, for Lillian Bagala, product distribution initiatives like that in Scotland and tax holidays for pad manufacturers are good news.

“When girls ask for pads and are told to find an alternative because they’re too expensive, many of them end up being abused by men who can support them. They sleep with them, and where does that end? Teenage pregnancy,” she says and adds that the focus of conversations around gender equality tends to be on maternal health or women in leadership, and that getting funding for menstrual health is difficult.

“There’s so much talk about economic empowerment, but how do we empower women when they can’t ask for pain medication because of the shame, and when their mothers can’t help them with period products? These initiatives keep girls in school,” Lillian says plainly.

“The shame is universal and the silence a global rule,” Anna writes in It’s Only Blood. When she started working on the book, she says, she wasn’t able to say the word ‘menstruation’ without lowering her voice. That’s changed over the years – proof that talking helps. “It matters,” she says. “It matters whether I lower my voice or not when I talk to my kids about periods. We can’t just break free from ancient patterns of shame, but we can take small steps, and that can make a difference.”

Linnea Dunne is a freelance journalist.

Period activists around the world

»We’re not used to putting things inside our vagina. That’s a taboo in itself«

Rachana Bunn

Co-Founder and Executive Director of Klahaan, Phnom Penh, Cambodia.

“I’m in my late 30s, and I only fully understand menstrual hygiene and care in the past five years or so! When I grew up, no one told me how to use pads properly. My mother wouldn’t tell me, we wouldn’t discuss it among friends. It’s a taboo topic”, says Rachana Bunn, Executive Director for Klahaan, an organisation that campaigns on a range of issues affecting women in Cambodia, menstruation being one of them.

“Most schools only have one or two unisex toilets, there’s a lack of clean water and soap, and there’s nowhere to secretly dispose of pads,” says Rachana, adding that the prohibitive cost of pads means that many girls use each pad for too long. Emerging social enterprises are trying to promote the menstrual cup and reusable pads, but that’s a huge up-front cost. “Also, we’re not used to putting things inside our vagina. That’s a taboo in itself.”

The culture of silence is the perfect breeding ground for misinformation, with the knock-on effect that inappropriate cleansing regimes and improper use of pads lead to infections. An adapted, comprehensive sex education curriculum was recently introduced in schools, but Rachana says that the delivery is questionable at best, as teachers are uncomfortable. “There are a lot of myths, like that you shouldn’t shower when you’re on your period, and they’re spreading as quickly as we’re able to debunk them.”

»With poverty comes period poverty«

Gabby Edlin

Founder of Bloody Good Period, London, UK

It started as a whip-around on Facebook. Today, Bloody Good Period is a growing charity that provides period products to those who can’t afford them, and menstrual education to those less likely to access it.

“People often believe that poverty is something that happens in Africa and India, because that’s where we’re told poverty is, but there’s a huge amount of poverty in the UK,” says founder Gabby Edlin. “With that comes period poverty.”

At the heart of Bloody Good Period is the outreach work the organisation does with refugees and asylum seekers. “They’re the most marginalised and most forgotten group in our society,” says Gabby, explaining that asylum seekers in detention centres in the UK are given £30 a week to live on. “They’ve already been forced into a situation where they’re not even allowed to feel human. Having your period then often feels like the straw that breaks the camel’s back.”

The covid-19 pandemic has made an already desperate situation significantly worse, with the charity giving out around six times the amount of products it did previously.

“And that’s not to say that that’s the limit of the demand. More people are falling into poverty. “You’d expect a country as rich as Britain to be further along, that it’s not a country that struggles to feed people — but apparently it is.”

»Many people have to choose between food or pads«

Sharon Kurgat

Nairobi Kenya

When Sharon Kurgat got her period, aged 13, her mother had spoken to her about it several times. She knew well what to expect, and the worst part of it was “the trauma of the pain”. That wasn’t the case for all her peers though, she explains.

“Many young girls get false information. They’re told that when you get married and have sex, your menstruation will stop – so when they get their period they think it’s time to get married to get rid of it. When I got my period, most girls my age were married off.”

Access to period products is a class issue, and Sharon feels lucky that getting pads was never an issue for her. “For the other girls in our village back home, that’s a key issue. They’re so expensive, many people have to choose between food or pads,” she says, adding that the bathrooms in school were “far from hygienic, but we managed”.

Since starting university in the city, Sharon has made a conscious effort to talk to other girls about menstruation in order to remove some of the stigma. She now runs an initiative called Period drive, which collects and distributes pads to young girls in rural areas.

“Things are getting better, and there are more period initiatives now, especially in Nairobi. But fewer initiatives are reaching the rural villages, and girls are still getting married as a result of getting their periods,” she explains. “At the moment, I’m working hard to find supporters to buy pads to distribute to these girls.”

»I had a crippling fear of tampons«

Ellie Horgan

West Cork, Ireland

“The first time I heard any real information about periods was probably the obligatory sexual education class all students had to attend in our last year of primary school,” says Ellie Horgan, who is now in her last year of secondary school. “The boys were asked to leave the room, and I remember being told not to tell them about what we had been discussing. There was a real sense of secrecy.”

As they got older, Ellie and her friends started talking more about periods as a natural part of life, and she says that the school she is in now has “a brilliant attitude towards menstruation”, with free period products as well as advice available to anyone who needs it. Yet, she describes the sex education in Ireland as “sub-standard at best. There’s undoubtedly a heavy, oppressive, Catholic influence on the way we teach young people about sex, consent, gender… There’s a huge culture of shame, and educators have to work within the boundaries of a curriculum set decades ago.”

Her criticisms range from a lack of information about the range of period products available – “I had a crippling fear of tampons, as we’d been taught about the dangers of TSS” – and a culture of dismissing menstruating people’s pain and symptoms.

“I was told that it was normal to have excessively heavy bleeding, and pain bad enough to make me nauseous,” she says. “I overlooked these issues for a long time, when I should have sought medical advice, because of that same stigma.”

»The doors wouldn’t lock«

Fiona Ibanda

Kampala, Uganda

“I was in class when I stood out of my seat and realised I had stained my uniform. There was a burst of laughter from all the children, including the boys, and I felt horrible,” says Fiona Ibanda. More than two decades have passed since the day she got her first period, but she remembers it clearly.

Fiona had never been taught about periods. The sex education for girls, she explains, revolved around a tradition of the elongation of the labia. “Ladies are supposed to pull the labia for an improved sexual experience, so the classes were dedicated to this rather than telling us about periods. Then of course I grew up and realised that wasn’t really for me – it was just what men demanded.”

She was lucky, she says, because her father was “a free-spirited guy” who worked for the UN. “He was the first person who ever bought me pads. He showed me the section and said ‘I don’t know much about pads, but I think this would work’.”

Back then, her school had pit toilets and there were no bins. “The doors wouldn’t lock either, so you had to hold onto the door. There were some special bathrooms separate from the communal bathrooms, but I never used those. The stigma would’ve been too much,” Fiona says, adding that things have improved and most toilets have dedicated bins for pads now.

By far the biggest issue, she says, is cost. “I struggle to access the particular pads I need, so I can only imagine what it must be like for girls in rural areas. Many of these girls don’t go to school, because they can’t afford pads. They use cloth or tissue, and they don’t want the embarrassment of a stain.”

OKAY FOR OKY

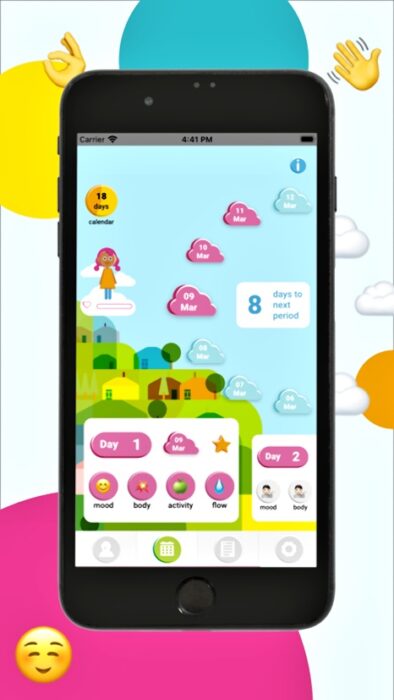

New peppy apps are designed to decrease period stigma and to provide knowledge and information.

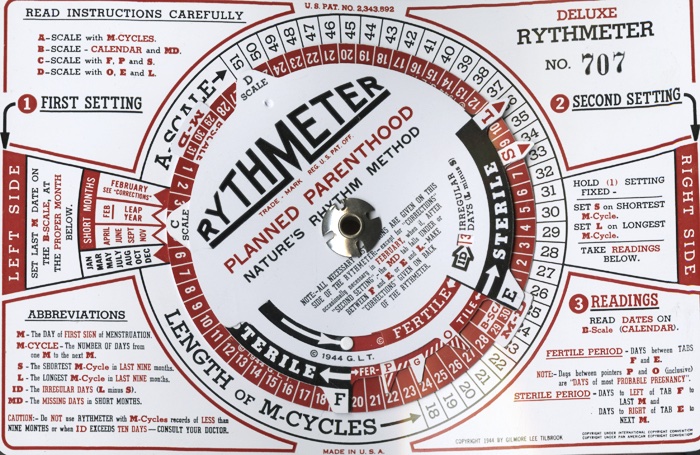

1945 there was the analogue fertility calculator Rythmeter, which allowed users to calculate their fertile days. Today, a wide range of mobile apps can assist those who want to keep track of their menstruation and fertility, and the market for apps has completely exploded. Almost 400 different menstruation apps were available for Australian women to download, a study showed in 2019.

At the same time, critical voices are raising concern that some apps share your personal data with third parties, such as Facebook.

But not all menstruation apps are developed for commercial purposes. United Nations International Children’s Emergency Fund, Unicef, has launched the free menstruation app Oky, with the purpose of spreading information about menstruation to girls and women in low-income countries.

Research has shown that many girls in Indonesia don’t know what is going on when they first get their period, and that it can be hard to find accurate information on the Internet. Oky, which has been developed in cooperation with young girls in Indonesia and Mongolia, has a peppy, gamified design that allows the user to learn more about the menstrual cycle and menstrual hygiene. Unicef is hoping that, over time, the app will decrease harmful stigmas concerning menstruation.

Karolina Bergström